An old widow named Helen lives in a small cottage in a small village in England. This is her hometown and she has moved back after 60 years living in Australia. She lives alone with her memories. She knows no one in the village and no one knows her.

She walks down the hill and into

town once a week to buy a few vegetables, a meat pie, yogurt, and a pastry for

a treat, all she can carry back home. Sometimes she stands in her living room

and looks out the curtains, watching her neighbors. She has developed a strange

habit of poking about in people’s discarded garbage, to see if there is anything

interesting she can bring home. Just a strange old woman.

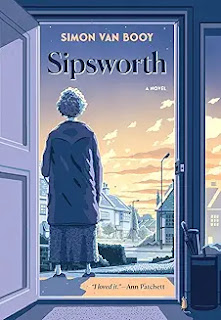

Helen is the protagonist of Sipsworth,

a novel by Simon Van Booy (2024), a story of an old woman and a mouse. It has

insights about aging that are worth reflecting on.

As the story opens, Helen has

pretty much given up on life and is waiting for death.

“Returning

after sixty years, Helen had felt her particular circumstances special: just as

she had once been singled out for happiness, she was now an object of despair.

But then after so many consecutive months alone, she came to the realization

that such feelings were simply the conditions of old age and largely the same

for everybody. Truly, there was no escape. Those who in life had held back in

matters of love would end up in bitterness. While the people like her, who had

filled the corners of each day, found themselves marooned on a scatter of

memories….”

“She isn’t

taking any medicine, nor does she need and creams, powders, tonics, or

lozenges. The only real proof of her advanced age are a chronic, persistent

feeling of defeat, aching limbs, and the power of invisibility to anyone

between the ages of ten and fifty.”

One night things change for Helen.

She watches from her window as a neighbor hauls some boxes out to the curb to

be carted away as garbage in the morning. She waits until he leaves and all is

quiet in the neighborhood, then she sneaks across the street for a peek. Among

the assembled items she finds an old fish tank filled with plastic water toys

and a few boxes. One of the toys reminds her of something her son once owned.

So, with a great deal of effort, she lifts and carries the tank back to her

house and deposits it on her living room floor. She then goes upstairs to take

a bath, worn out by the activity.

Once recovered from her adventure, she discovers a mouse in a box in the bottom of the tank. It shocks her; she has no desire to share her home with a rodent. But over the next two weeks, the woman and the mouse make a mutual connection. She names him Sipsworth. Her new responsibility to care for the critter forces her into the village to meet people—the clerk at Ace Hardware, the librarian (for a book on caring for mice), a vet, and, eventually, medical personnel in the local hospital as Sipsworth has an emergency that needs surgery. The book highlights the need all mammals (including humans) have for relationship and the possibility for change at any age.

But something else in the story

spoke to me. In the beginning we have the picture of a solitary old lady, set

in her ways, living in her memories, and developing some strange habits. It’s a

stereotype of a typical old person and, although I felt sympathy, I perceived

her as pathetic. But as the story nears its climax, the nurse in the hospital

recognizes her name, Helen Cartwright, and realizes that she was once the Head

of Pediatric Cardiology of the Sydney General Hospital and inventor of the

Cartwright Aortic Stem Valve, used to save the lives of hundreds of people. She

was famous in her day.

This, of course, changes the way

people now see this strange old woman. And it certainly changed the way I had

been reading the story. I was surprised, but I noticed there were hints all

through the story that things were not as they seemed.

I’ve experienced being treated as

an “old person” in the doctor’s office and the grocery line. I’ve experienced

being invisible in other social settings. I’ve wanted to say, “There’s more to

me than my wrinkles and walking stick!” But, of course, I don’t say that. I

don’t say anything.

And I take joy in the fact that

where I’m living now, I’m surrounded by friends and people who take the

trouble to know one another. Age doesn’t matter, since we’re all old!

But more than wanting people to

see me as a person rather than as a stage in life, I’m asking myself how I see

other people, especially other older people I don’t know. I’m realizing that I

often look at them with the same stereotypical perspective, especially if they

“look” old and grumpy and mussed up. I don’t feel compelled to get to know

them. They aren’t attractive.

(How I perceive young women with

purple hair and noses rings is much the same problem.)

I feel a sense of conviction.

Helen looked old and grumpy and mussed up. And I think I do too at times.

Learning how to see people as God sees them isn’t automatic. It’s hard. It’s

something to be aware of and to work at.

A person’s age and how they look

don’t define them. People are full of surprises. Especially old people. I don’t

want to miss out on any of it.

No comments:

Post a Comment